⚡ Quick Answer

Pick Godot or Unity. Make Pong. Then make something slightly bigger. Then publish it. Skip the 40-hour courses and just start building things. You’ll learn more from finishing three ugly games than from watching tutorials forever.

📋 In This Guide

Everyone wants to make games. The dream is universal: build something people play, maybe even something that pays your rent. But the path from “I want to make a game” to “I shipped a game” is littered with abandoned projects, tutorial hell, and scope creep disasters.

This guide is the roadmap I wish I had. Not theory. Not motivation. Just the actual steps, in order, with realistic expectations baked in. By the end, you’ll know exactly what to learn, what to skip, and how to actually finish something.

What You Actually Need to Start

Let’s kill some myths first.

You don’t need a computer science degree. Most indie devs are self-taught. The concepts you need can be learned in weeks, not years.

You don’t need to be good at art. Plenty of successful games use simple shapes, pixel art you can learn in a weekend, or free assets. Undertale was made with basic sprites. Vampire Survivors uses asset packs.

You don’t need money. Every major game engine is free to start. Free assets exist everywhere. You can publish on itch.io for free.

What you actually need:

- A computer (even a 5-year-old laptop works for 2D games)

- A free game engine (we’ll pick one in the next section)

- Time (even 30 minutes a day adds up)

- Stubbornness (this is the real requirement)

That last one matters most. You will get stuck. You will feel like you’re not making progress. The people who finish games aren’t smarter, they’re just more stubborn.

Step 1: Choose Your Game Engine

A game engine handles the boring stuff (rendering graphics, detecting collisions, playing sounds) so you can focus on making your actual game. You need one. Here are your real options in 2026:

Godot

Best for: Solo developers, 2D games, learning fundamentals, people who want to own their tools.

Godot is completely free and open source. No revenue share, no strings attached. The editor is lightweight (around 40MB), and the scripting language (GDScript) was designed specifically for games, so it’s easier to pick up than C#.

The 2D tools are genuinely excellent. For 3D, it’s improving fast but still behind Unity and Unreal.

Unity

Best for: Mobile games, teams, people who want maximum job opportunities, 3D projects.

Unity is the industry workhorse. Tons of tutorials, massive asset store, and most game dev jobs ask for Unity experience. It uses C#, which is also useful outside games.

The pricing drama from 2023 scared some people off, but they walked it back. For most indie devs, it’s still free until you’re making real money.

Unreal Engine

Best for: High-end 3D, people with existing C++ knowledge, AAA-style visuals.

Unreal makes gorgeous games but has the steepest learning curve. The visual scripting (Blueprints) helps, but you’ll eventually need C++ for serious projects. Probably overkill for your first game.

🎯 My Recommendation

Solo or just starting? Go with Godot. It’s the fastest path from zero to playable game.

Want industry skills or making mobile games? Go with Unity. More tutorials, more jobs, bigger ecosystem.

We wrote a detailed Godot vs Unity comparison if you want the full breakdown.

Pick one and commit. The worst thing you can do is spend weeks “researching” engines instead of making games. They all work. The best engine is the one you actually use.

Step 2: Learn the Fundamentals (2-4 Weeks)

You don’t need to master programming before making games. You need to learn just enough to be dangerous, then learn the rest as you go.

Week 1-2: Basic programming concepts

- Variables (storing information)

- Conditionals (if this, then that)

- Loops (do this 10 times)

- Functions (reusable chunks of code)

That’s it. Four concepts. Everything else builds on these.

Week 2-4: Engine basics

- How to navigate the editor

- Creating objects and scenes

- Making something move with player input

- Detecting when things collide

- Playing a sound

Follow ONE beginner tutorial series for your engine. Not five. One. Complete it, even if it feels slow. Then stop watching tutorials.

⚡ Avoid tutorial hell: Watching tutorials feels productive but isn’t. After your first series, learn by building things and Googling specific problems when you hit them.

Step 3: Your First Real Project

Your first project should be a clone of a simple classic game. Pong, Breakout, Asteroids, or Flappy Bird. I know it’s not exciting. That’s the point.

Why clones work:

- Design is already done (no creative decisions to paralyze you)

- Scope is known (you can’t accidentally make it too big)

- Success is clear (does it work like the original?)

- Thousands of tutorials exist if you get stuck

Definition of done:

- The core mechanic works

- There’s a win/lose condition

- Someone else can play it without you explaining anything

- It doesn’t crash

That’s it. You don’t need menus. You don’t need multiple levels. You don’t need good art. Ugly and finished beats beautiful and abandoned every time.

Common First-Project Mistakes

Feature creep: “My Pong clone should have power-ups, multiple ball types, a level editor, and online multiplayer.” No. Stop. Make Pong. Two paddles, one ball, a score. Ship it.

Art paralysis: Spending weeks on pixel art before the game even works. Use colored rectangles. Make them pretty later (or never, that’s fine too).

Restarting: “My code is messy, I should start over with better architecture.” Your code is supposed to be messy. You’re learning. Keep going.

Perfectionism: The game needs to ship. Not be perfect. Finished is a feature.

Step 4: The Core Skills Loop

Game development has three pillars: Programming, Design, and Art/Audio. You don’t need to master all three. You need enough of each to make your games work.

Programming

This is where you’ll spend most of your learning time. Focus on:

- Game loops and state management

- Collision detection and response

- Basic physics (gravity, velocity, acceleration)

- Data structures (lists, dictionaries)

- Debugging (you’ll do a lot of this)

You learn these by building games, not by reading about them. Each project teaches you something new.

Design

Design is about making your game feel good to play. It’s the hardest to teach because it’s mostly about intuition you develop over time.

- Play lots of games critically (why is this fun?)

- Read postmortems from other developers

- Playtest with real people and watch them (don’t explain, just observe)

- Study “game feel” and “juice” (tiny details that make actions satisfying)

Art and Audio

Good news: you can make great games with minimal art skills. Options:

- Use assets: itch.io and OpenGameArt have thousands of free assets

- Simple art styles: Geometric shapes, pixel art, or minimalist designs

- Commission or collaborate: Find an artist when you have a working prototype

- Learn basics: Even 10 hours of pixel art practice goes a long way

For audio, use free sound effect libraries and royalty-free music. Swap in better assets later if your game takes off.

Step 5: Your Second Project (The Real One)

After finishing your Pong clone, you’re ready for something slightly more ambitious. Not your dream game. Something in between.

Good second projects:

- A simple platformer with 5-10 levels

- A top-down shooter with 3 enemy types

- A puzzle game with one core mechanic

- A tiny RPG with basic combat and exploration

Add ONE new thing you didn’t do in your first project. Maybe that’s saving/loading, or a simple menu system, or a new type of gameplay. Not five new things. One.

This is also where polish starts to matter. Add screen shake when things explode. Add sound effects for every action. Make buttons respond when you hover over them. These details take a game from “prototype” to “something you’re proud of.”

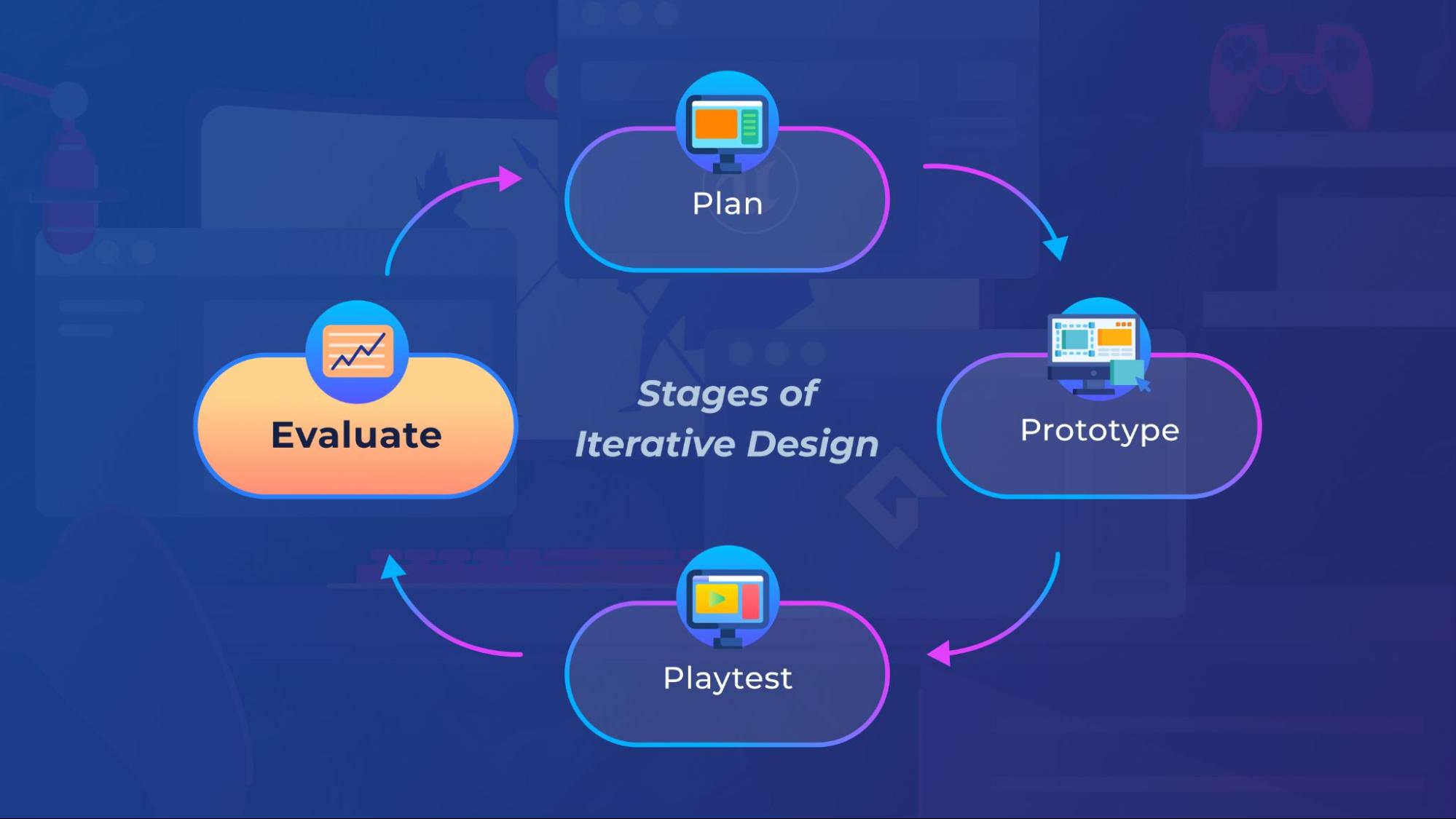

Playtesting becomes critical. Have someone else play your game while you watch. Don’t explain anything. Notice where they get confused or frustrated. Fix those things. Repeat.

Step 6: Publishing Your Game

You made a game. Time to put it in front of people.

itch.io (Start Here)

Free to upload. No approval process. Supportive community. This is where your first games should live. The audience expects indie experiments, not AAA polish.

Upload your game, write a short description, add a few screenshots, done. You’re a published game developer.

Steam

$100 fee to publish. Much larger audience but also much higher expectations. Save this for your third or fourth project when you have something more substantial.

Steam’s algorithm rewards games that get wishlisted before launch. If you’re going Steam, start marketing months before release.

Mobile (iOS/Android)

Apple charges $99/year. Google charges $25 one-time. Mobile is competitive and dominated by free-to-play, but casual games can still find audiences.

Both platforms have extensive review processes. Budget extra time for approval.

Marketing Basics

Marketing sucks. Nobody wants to do it. But games don’t sell themselves. Some basics:

- Start sharing development progress early (Twitter/X, Reddit, Discord)

- Make a short GIF or video showing gameplay

- Post to relevant subreddits (check their rules first)

- Consider game jams for visibility

- A simple landing page or presskit helps journalists/streamers

Marketing is easier when your game has a clear hook. “Vampire Survivors but with fishing” is more shareable than “a fun roguelike.”

The Realistic Timeline

Let’s be honest about how long this takes.

First tiny game (Pong clone): 2-8 weeks

Second small project: 2-4 months

Something you’re genuinely proud of: 6-12 months

A game people actually buy: 1-3 years (maybe longer, maybe never)

These timelines assume part-time work. A few hours per day or weekends. If you’re doing this full-time, you can compress them significantly.

The biggest factor isn’t talent. It’s consistency. Someone who works 30 minutes daily will outpace someone who does 8-hour weekend sprints followed by weeks of nothing.

This is a marathon, not a sprint. Set sustainable habits.

Resources That Actually Help

YouTube Channels

- Brackeys (Unity, though he stopped uploading, the archive is gold)

- GDQuest (Godot, excellent quality)

- Game Maker’s Toolkit (Design theory, not coding)

- Sebastian Lague (Advanced topics, beautifully explained)

Communities

- r/gamedev (general discussion)

- r/godot or r/unity (engine-specific help)

- Godot Discord and Unity Discord (official servers)

Free Assets

- itch.io/game-assets (huge collection, free and paid)

- OpenGameArt.org (all free, varying quality)

- Kenney.nl (high-quality free assets)

- Freesound.org (sound effects)

Game Jams

Game jams (timed game-making events) are the best way to force yourself to finish something. Try:

- Ludum Dare (48/72 hours, runs twice yearly)

- GMTK Game Jam (48 hours, huge participation)

- Weekly jams on itch.io (lower stakes, good practice)

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need to be good at math?

For most games, no. Basic algebra and geometry (angles, distances) cover 90% of what you’ll need. Engines handle the complex math. You can learn specific concepts when projects require them.

What programming language should I learn?

Learn whatever your chosen engine uses. GDScript for Godot, C# for Unity, C++ for Unreal. Don’t learn Python or JavaScript first hoping it transfers. Just go straight to the engine language.

Can I make [specific type of game]?

Probably, eventually. But don’t start with your dream game. Start small, build skills, then tackle ambitious projects. Your dream game deserves the skills you’ll have in a year, not the skills you have today.

How do I not quit?

Small projects. Finish them. The dopamine hit of completing something keeps you going. Also: find a community, set small milestones, and remember that every game developer has dozens of abandoned projects. It’s normal.

Should I go to school for game development?

Maybe, if you want to work at a studio and need the credential. For indie development, probably not. The money is better spent on living expenses while you build a portfolio. Shipped games matter more than degrees.

Start Today

Here’s what to do right now:

- Download Godot or Unity

- Find a beginner tutorial for your engine

- Follow it for one hour

- Tomorrow, do another hour

Don’t research more. Don’t read more guides. Don’t compare engines again. Just start. The roadmap only works if you walk it.

In three months, you’ll have a finished game. In a year, you’ll have several. In two years, you might have something people pay for. But it all starts with opening that engine and making a rectangle move across the screen.

Go make something.